World Water Day: The True Cost of Conventional Cotton

The production of consumer goods is a crippling drain on the world’s water resources. We reveal the price we pay for conventional cotton and look to the inspiring alternatives already available.

World Water Day has never been more vital. As worldwide population expands and global temperatures continue to rise, already struggling communities are having their livelihoods further restricted. The developed world has (with some exceptions) been able to remain undisturbed, the scarcity of water a distant and detached issue. It can be strange to even imagine something as a resource when it literally falls from the sky, but indeed water is a strange resource; globally abundant, distributed incredibly unevenly, utterly vital for survival. As with so many other issues, drought may only seem an immediate compelling problem when it’s on the doorstep.

No matter the physical distance, the problem isn’t a detached environmental issue for shops or manufacturers of goods. Perhaps it’s due to the advice we’re given in the UK as our plentiful water supplies begin to dry up, but there is an accepted mentality when it comes to saving water, and it lets industry off the hook. Consciousness is entirely focused on the consumer and the home – hose-pipe bans, brushing your teeth with the tap off. These are helpful measures to be sure, but measures that can only go so far to solve the problem. Industry and agriculture account for a whopping 90 percent of the world’s water use, and it’s these two fields that customers may feel they have no power over. It’s an attitude that the most cynical and close-minded organizations ruthlessly exploit in the name of continued profit.Every product that you purchase has one cost on the label. The second is never shown. The water cost. From skinny jeans to washing machines, everything needs a flow of H2O in its creation cycle. The amount will vary massively, but it’s not just about the liter number. No matter how thirsty a crop or product is, if it’s brought to life in Seattle it’s going to struggle to gulp down all the rain. It’s location, location, location when you’re calculating the water cost.

Money talks. It talks louder than ecology has ever been able to. And where there’s any opportunity for industry to exploit any resources a region has, it tramples over the simplest and sanest environmental concerns. When an otherwise dry country has one or two lush supplies of water, it’s natural that it should be drawn from the proverbial well. And then a little more is withdrawn. And then, seeing as it’s all just sitting there, how about we intensify things, bring in the cash crops that really spin the money? What could go wrong?

One material stands apart from others when it comes to water cost. Conventionally produced cotton is the dominant fabric grown on every continent and worn in every country across the globe. Up to 60 percent of all women’s apparel contains some kind of cotton blend and that number rises to 75 percent for men. An amazing 2.5 percent of the earth’s arable land is used to grow the plant. To its credit it is a fantastically versatile fabric; soft, durable and most of all abundant. But its utility can come at a high price.

Cotton is one of the thirstiest crops in the world; each year 198 trillion liters of water is used in its production. It’s a crop that best suits tropical and sub-tropical environs, where it can find both the reliably powerful sunshine and a predictable supply of water needed for it to flourish. It’s not designed to grow in the driest regions of the world. But that doesn’t stop us from growing it. ‘Cheap’ cotton is fuelling unsustainable production and consumers commonly do not pay a price which reflects these costs. The damage can go beyond the usual or fixable. It can cause widespread ecological disasters.

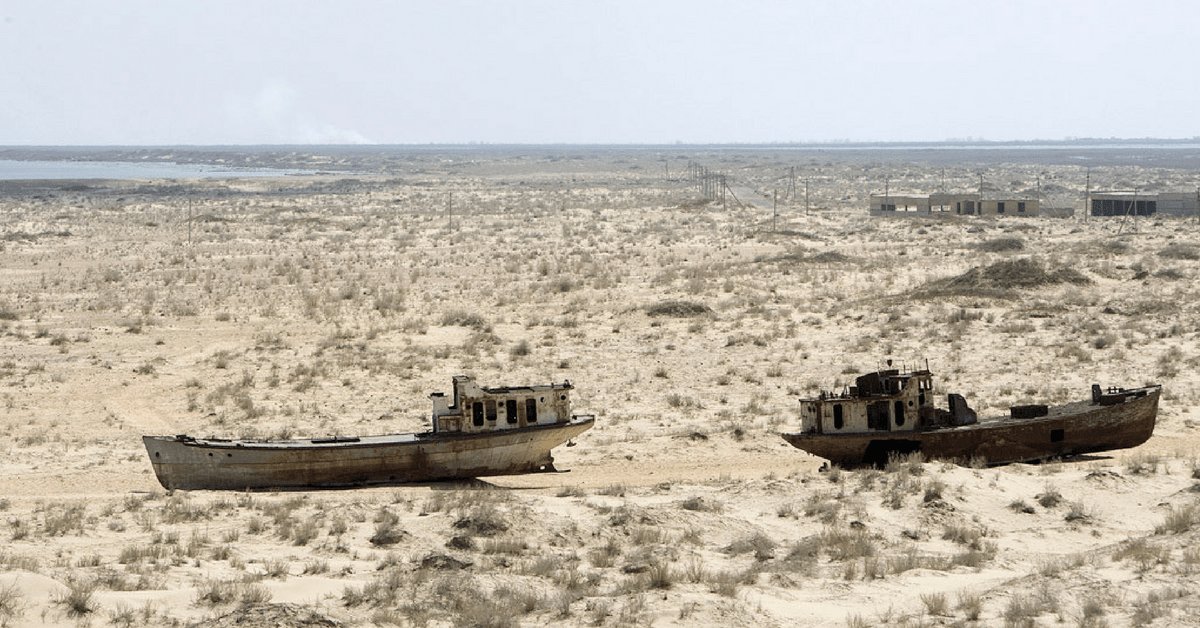

The Aral Sea: A Man Made Catastrophe

For thousands of years and up until the 1960s, the Aral Sea stood as the planet’s fourth largest inland sea. A regional oasis within arid Uzbekistan, the area surrounding it reveled in a stable existence. It was biologically diverse and resource rich; a fishing industry prospered alongside a small and sustainable agriculture sector.

Today, there is no Aral Sea. Two bodies of water remain, the North Aral and South Aral. Neither of these are large enough to match the top 50 lakes. On the other hand, since the 1960s Uzbekistan has climbed from a non-player in the cotton industry to one of the most prominent exporters in the world. In 1988 it became the world’s largest exporter of cotton. That lofty status couldn’t last, but then neither could the Aral.

In a Soviet chase to capitalize on the “white gold” ideal of cotton, the rivers that fed the Aral were heavily exploited for irrigation. Canals were hastily built in a bid to create an industry from scratch, speed prioritized over quality. In 1960, one imagines it would be difficult to gaze out across the vast expanse of the Aral Sea and imagine that its bounty could ever be depleted. But Uzbekistan is dry, and cotton is thirsty. With little rainfall, the crops would be fed nearly entirely by the Aral’s own supplies. It was really only a matter of time.

Uzbekistan remains the world’s sixth largest producer of cotton through one of the most water-intensive and wasteful cotton production systems in the world. More than 1.34 million hectares of land are under cotton cultivation, and cotton farms today consume around 16 billion cubic meters (m3) of water each year. Thousands of kilometers lie barren, a new desert littered with memories of decades gone. These effects aren’t news, they’ve been in the public domain for years and years. It’s important to only buy cotton with a labeled source, as this Uzbek cotton does manage to find it’s way into the global supply chain one way or another. We can help end it, with some good old-fashioned customer pressure.

Cotton In India: Historic Waste, A Positive Future

From the sixth largest producer of cotton to the behemoth that is India. Only narrowly behind China in the production stakes, India produces a massive 6.4 million tonnes each year. Their cotton story is different, more varied and less destructive, as one might expect in a much larger country supporting a population of 1.2 billion. In India’s agricultural story we can see the worst and the best of the industry, wasteful practices gradually being supplanted by the progressive thinking needed to live sustainably.

According to the Water Footprint Network, it takes an average of 22,500 liters of water to produce just one kilogram of cotton in India. The total supply of H2O required to feed India’s cotton exports in 2013 could supply the entire population with 85 liters of water every day, all year. Wasteful practices dating back to the colonial period are a burden on production – cotton growing heartlands are placed in the more unsuitable regions and with wasteful centralized irrigation systems. The dry states of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, which have very high evaporation rates, dominate production, whereas naturally wet states such as Bihar, Jharkhand and Orissa are cast aside.

Meanwhile, more than 100 million people in India do not have access to safe water. The conventional cotton growing process leans so heavily on chemicals and GM that the runoff water is rendered useless. By exporting more than one million tonnes of cotton in 2016, India also exported about 40 billion cubic meters of virtual water. This is the true cost of conventional cotton.

But there is light at the end of the tunnel here. Encouragingly, government officials have shown an interest in moving the cotton industry’s hub away from the dryer states, rather than doubling down on inefficient existent practices. Better still is the growing interest in the Better Cotton initiative; India is quickly becoming the home to the solution, the headquarters of the sustainable, organic cotton industry.

India currently produces two-thirds of the world’s organic cotton. However, this is just 2 percent of the country’s cotton acreage. It’s going in the right direction, but it will increase at a rapid rate if we as consumers vote with our wallets.